Quick note: In addition to being mentioned in the Economist’s most-read article of the prior weekend, How to Be a Grown Up was also selected by Oprah as the #3 best book for recent graduates!

So, if you know anyone who is graduating from college this spring, don’t forget to order it now as a gift.

In the book, I devote a whole chapter to communication skills, including a deep-dive into disagreements. But what happens when instead of disagreeing with someone else, you’re caught in the middle of a disagreement between two other people? You may be thrust into the role of a mediator.

What follows is a communication technique that is more “advanced” than what I typically write about…

Mediation

Mediation is a fascinating topic. A lot of it is about understanding each side’s interests: using empathy (putting yourself in their shoes) to learn what it is they really want. It may not be what you first think—for example, in a divorce, one person wants money but the other wants custody—so this makes it possible to reach a resolution.

Empathy, though, is a necessary but not sufficient ingredient for conflict resolution. It’s one thing to have someone understand another person’s needs—but then, how do you get them to agree to put (at least some of) the other person’s needs above their own? To be willing to give a little, for the sake of a relationship?

In other words, how can you persuade someone to put aside their own ego and aim for something higher? Appeal to their better nature. Motivate them to tap into the part of themselves that is selfless and caring. Help them see the bigger picture.

How, exactly?

1. Make it feel like you’re on the same team

People are tribal by nature. They tend to rally around those who are similar, and identify common enemies to fight. You can’t ignore that part of a person’s nature; you must use it to your advantage. If you can evoke the sense that both of you are on the same side—part of the same tribe—you can activate what psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls “the Hive Switch.”

For each person in the conflict, make it clear that you have more in common than apart. Make it clear that you are fighting to achieve the same goals. And earn their loyalty by demonstrating what you have already done in service of those goals.

2. Set a high expectation for them to live up to

One of Dale Carnegie’s famous insights from How to Win Friends and Influence People is: don’t criticize. Whereas criticism makes a person wilt, positive encouragement makes them bloom. Carnegie goes further, illustrating one of the deepest forms of positive encouragement:

If you want to improve a person in a certain respect… give them a fine reputation to live up to, and they will make prodigious efforts rather than see you disillusioned.

In other words, if you make it clear that you believe in someone’s capacity for greatness, they will work hard to prove you right.

An illustrative story

Toward the end of the Revolutionary War, American soldiers were complaining that they were not receiving their promised pay. A group of army officers further incited the unrest, and some of the Founding Fathers worried that this could be the beginning of a military coup. They were devastated to think that everything they had worked so hard to achieve might be ruined—in the eleventh hour—by some of the most patriotic people from their own side of the ocean.

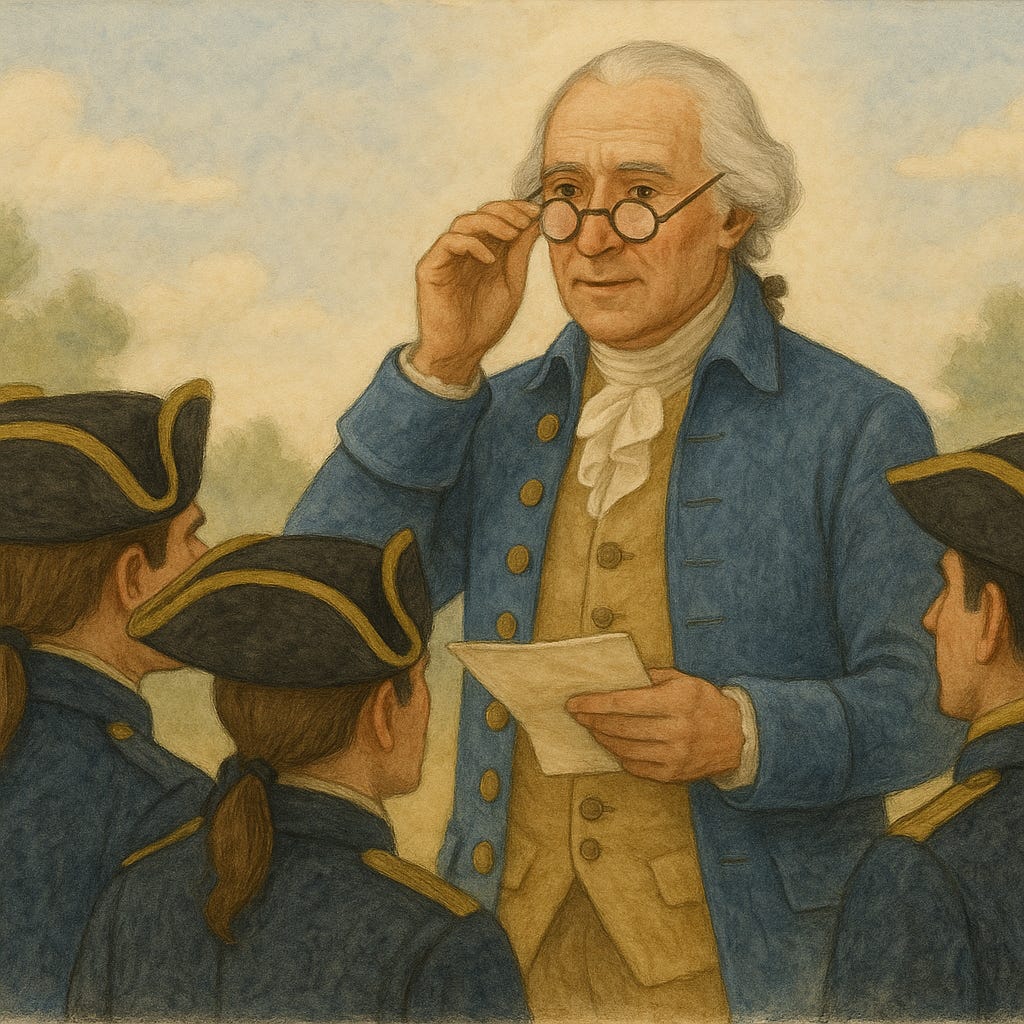

So, George Washington went to address the group of army officers. In a speech that has now become legendary, Washington demonstrated the use of both techniques to appeal to their better natures.

First, he quickly established that he and the officers were on the same team, declaring:

I was among the first who embarked in the cause of our common country; as I have never left your side one moment, but when called from you on public duty.

Second, he gave them a high expectation to live up to, saying:

I wanted a disposition to give you every opportunity, consistent with your own honor, and the dignity of the army, to make known your grievances.

The officers were reminded of their honor and dignity as principles to uphold.

Washington then utilized both techniques together in one action. Fumbling with a letter, he reached for his spectacles, which the officers had never before seen him wear. He said, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.” With this single gesture, he made it clear that (1) he had committed himself to the same cause as they had, and (2) he gave them a self-sacrificing ideal to live up to.

Did Washington’s tactics work?

If you’re enjoying life in the United States today, you probably already know the answer. The army officers unanimously agreed to compromise (by adopting resolutions pledging obedience to Congress); and Congress, in turn, agreed to compromise (by promising five years’ full pay).

Practical takeaway

If you ever find yourself in the middle of a conflict, try reaching out to both people individually. After helping them to understand each other’s interests, appeal to their better nature.

Try structuring your message as follows:

“I was concerned to hear that…” – establish that this conflict is bad for everyone

“We both want what’s best for our family/friend group…” – make it feel like you’re on the same team

“I know that you are a forgiving person / I know that you are capable of being the bigger person…” – set a high expectation for them to live up to

“I’m counting on you to…” – establish accountability, within the context of your personal relationship

Of course, not all conflicts are worth mediating—sometimes you’re better off removing yourself so you can live, as my wife and I like to say, a “drama free life.” But if you do hope to resolve one, give this a try and let me know what you learn.